This is the last part of a series of posts on meaning, like the meaning we could give to things or which we aim to find in life. Part 1 discussed absolute limits to meaning. Part 2 considered individualistic philosophical views, and Part 3 looks at the role communities can play. Among the three, it may come closest to reconciling meaning with life satisfaction and happiness.

No matter where and when we are born, there will always arise tensions between the individuum we are and the demands from the groups we are in, sometimes chosen and voluntarily, sometimes not. The earliest such conflicts are in the family. In mostly benign situations, our parents will ask us to commit to things we don’t want to do, like spending time with boring or awkward relatives. On a grander scale such bonding activities keep communities, like families, in good order, but we may not see this.

As we grow older, we form and join more communities, like that of our neighbourhood, classmates, friends, co-workers, parents, or fellow enthusiasts in spiritual, cultural, or sports clubs. The list of possible groups people can sort into, or form is endless.

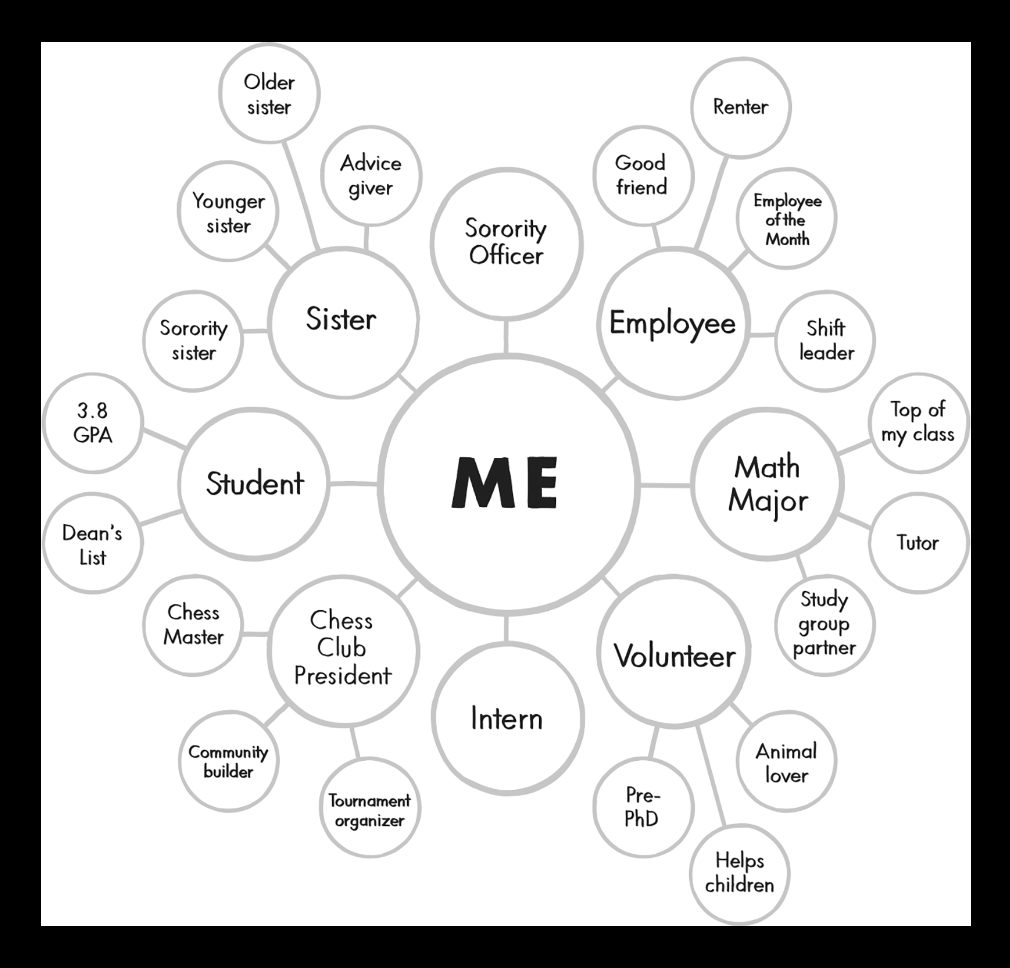

We take on different roles in the different communities. We are son, father, colleague, friend, etc. An example of a “membership profile” this can lead to (taken from the highly recommended book “Supercommunicators“) is shown below. The different communities we belong to often are a strong source of our identity. As such, communities can be a source for good, and given their nature, a way to connect with others.

However, society has its subtle, sometimes less subtle, and often perversive ways to “guide” us, sometimes even force us, into communities, like family structures or religious groups, by which I certainly not only mean particularly conservative and extreme bits of society.

Furthermore, behaviour in groups can be highly codified, or there are – sometimes imagined – strong expectations about desirable behaviour. If you belong to the group of dog walkers, you are expected to clean up after your pooch (good thing!). If you belong to the group of middle-class parents, you may be expected to move house just for your kids’ schooling (questionable).

I will briefly discuss conflicts which can arise in connection to communities below. However, and overall, we are social animals and we thrive in groups which support us or just make us feel good. For instance, spending time with friends is a key contributor to all sorts of wellbeing, and not having spent enough time with friends is a key regret of the dying (more on this below).

In Part 2, I discussed the hedonistic altruist – a somewhat abstract, theoretical, and individualistic fellow. Let’s see how this theoretical construct works together with the community perspective. Take a fictional character Serena, who is inspired by a dear real-world friendship. Serena has her passions, which are family and friends, and movies, music, and sex. Serena is married to a man but also bi-sexual. Based on this sparse profile she already has many identities making her part of several communities with her corresponding role, like daughter, wife, daughter in-law, kinkster, and a fan of the arts.

Serena deeply cares about her family, especially her elderly parents, but also local DJs who sometimes struggle to make ends meet. Taking the hedonistic altruist’s view, she enjoys family life and hanging out with friends, but she also contributes to each community by providing the support she can, like making arrangements for her parents when their health fails or donating money to local cultural groups. Taken together, she and her communities are thriving if everybody contributes, while everybody still can be an individuum.

However, Serena’s life is not without frictions. Parts of her family would like to see her as a mother, and her husband is not a particular fan of her sexual exploits. Managing those tensions are basically her challenges in life. Interestingly, they stem from the different expectations different people may have about a particular role. In the end, these can either be aligned, possibly through compromise, or somebody needs to leave a group, which can be painful.

On a bigger scale, this brings us to the larger conflicts of societies nowadays. These are often about identities, and how they are evolving over time, like family or gender roles. On even larger scales, inter-group conflicts are the bigger issue, where different group identities may seem impossible to reconcile. These are the challenges of our time. These will be discussed in a separate post at some point in the future.

Let us conclude on a positive note. While nothing has absolute objective value, people may be torn between their own desires and their urge to do good for others. Integration and involvement in communities can resolve this tension, creating win-win situations for everybody. Luckily, many modern societies allow their members to largely choose freely their identities and which communities to belong to.

Given the competitive and often hyper-comparative nature of modern economies, the flourishing within one’s chosen communities offers a path to meaning, fulfilment, and potentially happiness to all, importantly, independent of quantitative “success measures” such as income or social media impact. As such, finding one’s communities, contributing to them, and experiencing their support, may be an approach accessible to all to address the ills of modern societies, like loneliness, increased mental decease burden (especially among the young), or a general lack of meaning of the individuum.

Finally, the wish to have “had the courage to live a life true to myself, not the life others expected of me” is the number one point reported in the Regrets of the Dying.

Leave a Reply